By Mehreen Kabir

Written on: January 4, 2023

Last Updated: March 10, 2023

Introduction

In 1911, a famous Parisian fashion designer Paul Poiret organised an Oriental-inspired party named “The One Thousand and Second Night” (27).

“Your footsteps were muffled by the rugs, but you could hear the rustle of silk and satin costumes… suddenly a miniature firework flared from display from behind a bush, then another and another. It was like fairyland.”

Paul Poiret

A part of the setting in Paul Poiret’s 1002nd Night party – Source

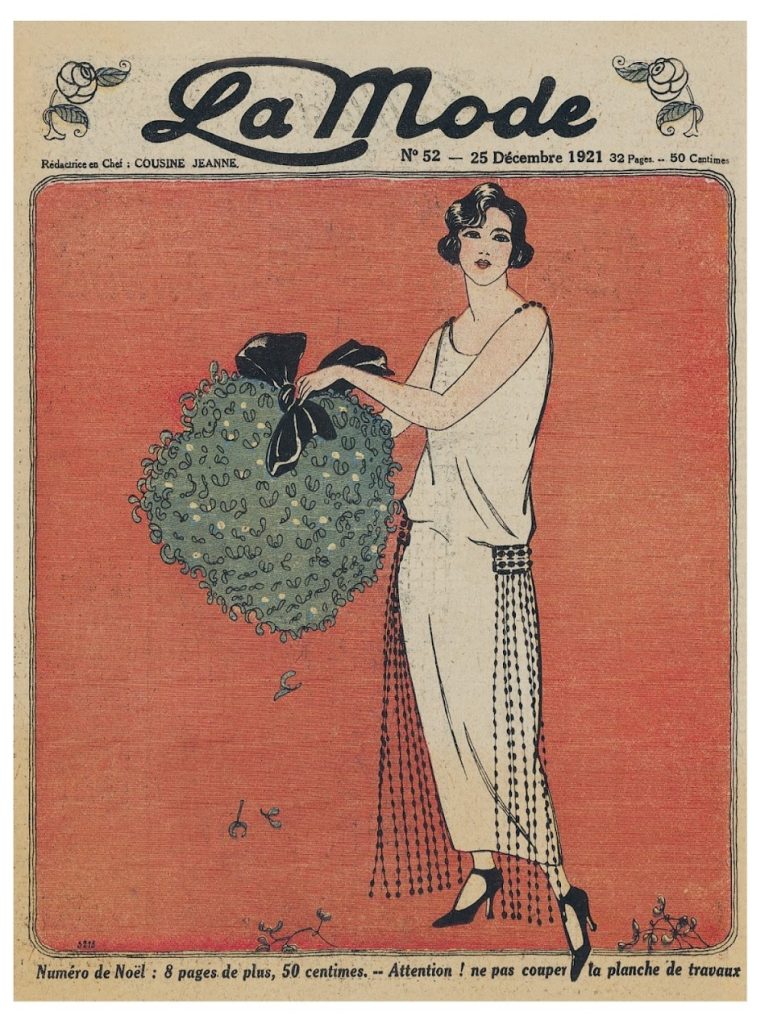

This perhaps set the stone for the Orientalist styles of 1920s fashion. While it is true that Western art and fashion have taken inspiration from Orientalism for a long time, it started to gain popularity in mainstream fashion in the 1920s(1). It can be said that Paul Poiret was primarily responsible for bringing Orientalist fashion into the mainstream(3).

Often touted as the “King of Fashion”, Poiret had a great fascination with oriental styles. He removed the need for corsets and created flowy dresses sewed in straight lines, taking inspiration from the Greek Chiton, Japanese Kimono and Middle Eastern Kaftan. His introduction of flat, two-dimensional silhouettes changed fashion for the next decade(3).

A coat in black wool and leather applique from Poiret’s collection, 1919 – Source

Orientalism in the Mainstream

There are many reasons for the rise of Orientalism in the mainstream during the 1920s. Europe had had trade routes with the East for centuries, and items like silks from China, shawls from India and kimonos from Japan were costly to import. Therefore, they were regarded as a symbol of wealth(10). In addition to that, places such as India and the Middle East were depicted as faraway lands of riches yet to be discovered(9). That is perhaps the biggest reason why Orientalism reached its height in the 1920s — after all, the 20s was all about displaying wealth and extravagance(11). European scholars of the time considered the “orient” to be such a place that cannot possibly be described through words and thus turned to other forms of creative expression such as fashion, dance etc(28).

“Our world is small next to the antique world, our celebrations are scanty compared to the frightening sumptuousness of the Roman rulers and Asiatic princes. Their ordinary meals would pass today for unbridled orgies… How, with the French language, so chaste, so glacially prudish, can we describe this frenetic fury, this large and forceful debauchery that does not fear mixing blood and wine, those two purples and the furious lust full of all the passion that the long Christian fast had not yet dulled?”

— Théophile Gautier(35)

The 1920s was also the time when people began to experiment with new things. Many started to question old Western Values due to the destruction caused by the war(12), prompting a shift in fashion and culture(13). People looked to movies for inspiration, and with the rise of Orientalism in media(14), the next step in fashion was clear. In fact, movies must have played a large role in Orientalist fashion trends. Before, Orientalism was mostly limited to paintings. With the growing popularity of going to the cinema(15), movies served as a much better way to sell the Orientalist fantasy.

Orientalism was also a marketing strategy to show off the riches of Europe’s colonies. This was especially true for the Middle East; Britain had been trying to colonize Sudan and Egypt during the 1880s and 90s, coincidentally matching up with the beginnings of mainstream Orientalism. After the first world war, Britain was involved in the partition of the Ottoman empire, intensifying efforts to know more about the region(9). The discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922(19) also led to a plethora of films about Egypt; all of a sudden, it was cool to be Egyptian.

Left: The American release of a German historical epic film regarding Egypt, 1922 – Source

Right: A Vogue advertisement touting “scent-bases known and used since the days of Tut-ankh-Amen”, 1923 – Source

In order to know about orientalist fashion, one must also familiarize oneself with the Ballet Russes. The Ballet Russes was a Ballet company founded in Paris in 1909 by Serge Diaghilev. The Ballet Russes quickly rose to prominence in Parisian fashion, sparking a public interest in the Russian and Oriental fashions donned by the dancers and even leading to artistic collaborations such as with Coco Chanel. In fact, many of the dancers were a part of Poiret’s clientele outside of their performances, showcasing the similarities between the two. While many of their performances took place before 1920, their influence carried on well into the 20s(29).

With all this being said, let’s plot in the most notable cultural inspirations!

Russia

The Ballet Russes, as it happens, took a lot of inspiration from Russian culture, especially Russian peasant traditions(30). Many Russians had also come to France following the Russian Revolution in 1917(31) and set up their own couture houses or worked for foreign ones(2).

The popular women’s silhouette in 1920s actually came from the Russian Kosovorotka(32) or Rubakha(33).

Left: A man wearing traditional kosovorotka – Source

Right: A fashion plate from 1922 – Source

Here, we can see the resemblance between the two clothing styles with their low waistlines and straight cut.

Right: Ethnic Russian dress known as “Sarafan” – Image by Ninaras – Own work, CC BY 4.0 (the original picture was cropped by the author of this article)

Left: A fashion plate from 1922 – Source

This outfit even has the classic Slavic red-white colour combination and sleeve shape. However, notice how the 20s outfit was made noticeably simpler compared to the picture above it. A big selling point for 1920s fashion was its mass production, causing designs to be less intricate compared to its ethnic inspirations(16).

Another element of fashion taken from Russia was fur(34). Natural fur was extremely expensive and a sign of wealth, perfectly fitting in with the 20s’ consumerist culture.

Louise Brooks dressed as a flapper with a fur trim coat, 1927 – Source

Africa

Josephine Baker, an extremely popular African-American dancer of the time, symbolized the popularity of both Black American and African culture. Her most notable performance, Danse Sauvage, translating to “Savage Dance”, sparked an interest in African fashion throughout France(18).

Josephine Baker in her banana costume, 1927 – Source

Josephine Baker had performed Danse Sauvage with only a string of bananas as her skirt, leading people to grow a fascination for the “savage” clothes and customs of African tribes.

While this did not convince the French into making their own skirts with bananas, another style of skirt from Africa did influence 20s fashion.

Top: Bantu women from Namibia – Image by Mahevo Saima – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Bottom: Josephine Baker dancing the Charleston wearing a fringe dress – Source

The iconic fringe skirts of the 20s most likely came from African skirts. These skirts were often donned while dancing in jazz clubs, a place often associated with African-American people.

Left: A Malawian tribe called Chewa – Image by Twiggalite – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Right: Violet Romer in a flapper dress – Source

Wider “fringes” were made from fabric, and they gave off the feel of a “savage” look that Europeans now longed to achieve.

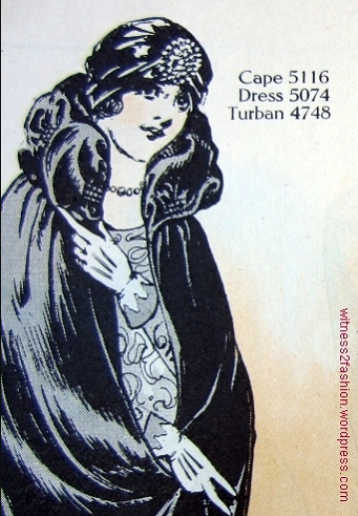

Left: An African woman wearing a headwrap or turban – Image by Emalikova – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Right: Edna Purviance wearing a turban – Source

Left: A fashion plate depicting a woman wearing a turban, 1924 – Source

Right: A South African woman wearing a colourful turban – Image by Alex Floyd-Douglass — Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

While the pictures of the African turbans above are modern, turbans have a long history dating back to pre-colonial Africa. For many, it was the only cultural remnant they had as they were shipped to Europe and the Americas as slaves(21). In the 1920s, the general public began to take an interest in silk turbans and headwraps as well.

Egypt and The Middle East

Top: Léon Bakst’s set design for Ballet Russes’ performance of Cléopâtre – Source

Bottom: Michel Fokine and Vera Fokina in Scheherazade, a Ballet Russes performance based on 1001 Nights, 1910 – Source

Whenever we think of “Orientalism”, it is mostly the Middle East that comes to mind. Large expanses of desert, belly dancing, spice markets in narrow alleyways all have origins in the Middle East. The 1920s were especially notorious for pushing Middle Eastern stereotypes in films(14) and fashion(13). We have already discussed the reason for this, so let’s take a look at the different inspirations!

Left: Popular Turkish clothing, 1873 – Source

Right: A dress made to be worn to Poiret’s 1002nd Night Party, 1911 – Source

Poiret was a big fan of harem trousers, a type of trouser originating in the Middle East, mainly Persia and Turkey(4). These harem pants were not exactly well received by much of the general public in Europe, with many considering it scandalous for women to wear trousers(5).

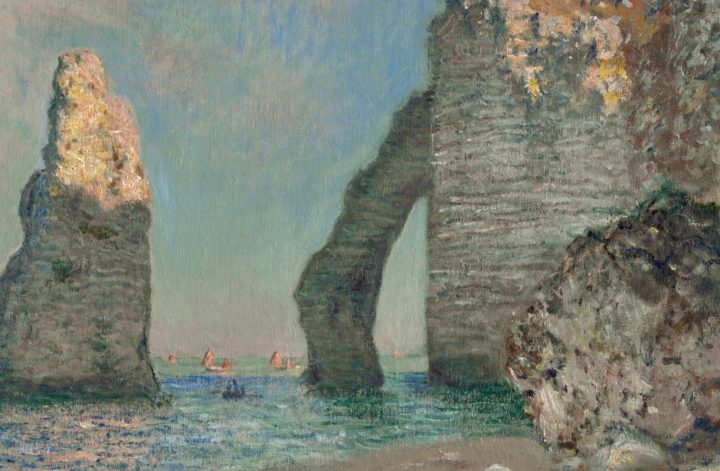

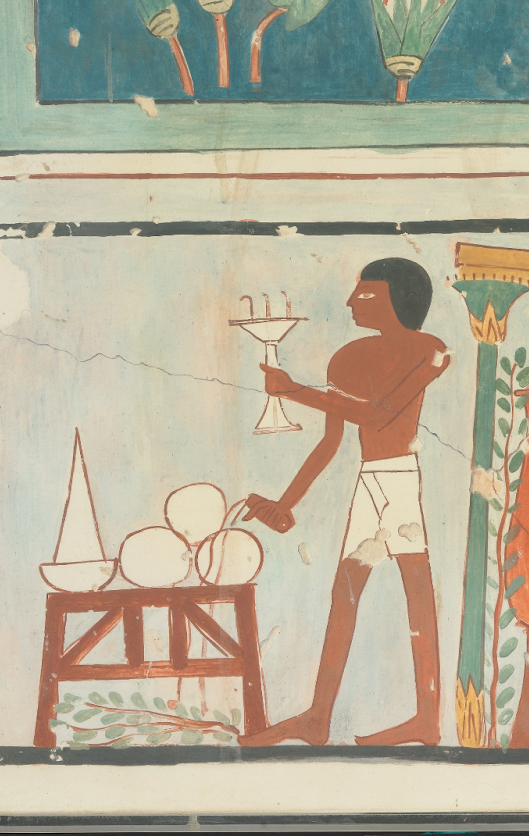

Left: Marion Wulz donning an Egyptian costume, 1920 – Source

Right: Brazier from the Burial of Amenhotep, 1479-1458 B.C – Source

Europe’s fascination with Egypt during this time can even be seen in model photography. Models donning Egyptian clothes often did poses resembling Ancient Egyptian art(17).

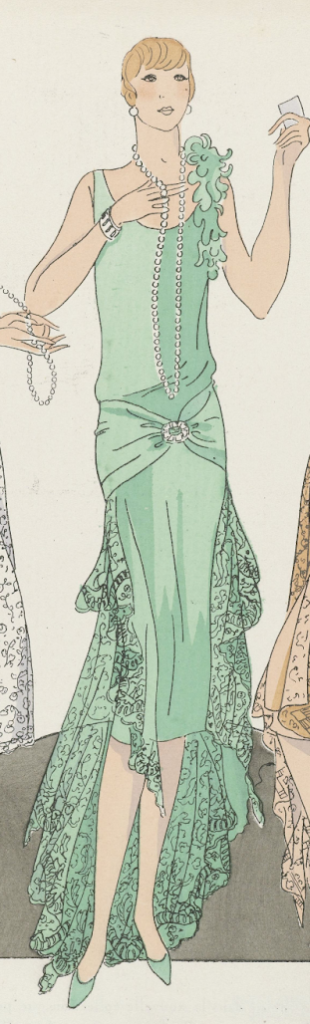

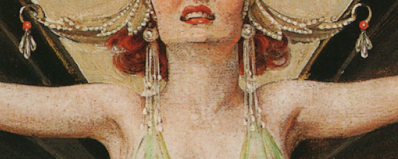

A painting of a flapper by Frank Xavier Leyendecker, 1922 – Source

Excerpts from “Ancient Egyptian, Assyrian, and Persian Costumes and Decorations” by Florence S. Hornblower and Mary Galway Houston, depicting Ancient Assyrian dress

Here, we can see that the hanging belt painted in Frank Xavier Leydecker’s painting is extremely similar to the ones worn in Ancient Assyria. The lines created by the pearls in Leydecker’s painting create a similar flow of the dress as the sketch of the Assyrian costume on the right. Using pearls to create the lines instead of the traditional way of gathering cloth not only creates a more opulent image, but also allows the model to show more skin.

Left: Fashion Plates, 1925 – Source

Right: An excerpt from “Ancient Egyptian, Assyrian, and Persian Costumes and Decorations” by Florence S. Hornblower and Mary Galway Houston, depicting ancient Egyptian dress

Here is another example of how designers took inspiration from cultural clothes. Once again, less material was used in the 1920s dress to make it more practical and cut down on cost.

Actress Alice Joyce wearing a beaded dress, 1926 – Source

An excerpt from “Ancient Egyptian, Assyrian, and Persian Costumes and Decorations” by Florence S. Hornblower and Mary Galway Houston, depicting common designs used in Ancient Egypt.

The discovery of Ancient Egyptian artefacts led to the use of common Egyptian motifs in clothes, as seen above. The beaded motifs in Alice Joyce’s dress especially resemble the illustration labelled “a”.

Left: Garment of Senebtisi, a beaded apron, 1850-1775 B.C – Source

Right: An excerpt from “1920s Fashion Scrapbook” depicting a fashion plate, 1921

Some designs were even taken from specific artefacts found in excavations. The beaded apron on the left was supposed to be worn in a similar fashion to the hanging beads of the 20s dress, except the Egyptian garment would have covered the front part of the dress as well.

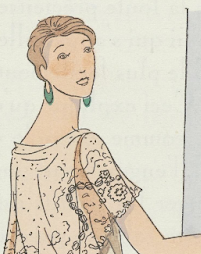

The Mediterranean

The loose sleeveless silhouette associated with 1920s dresses took inspiration from the chiton originating in Greece. Short chitons were usually worn for exercise or physical labour(30). Similarly, the chiton’s breathable nature and convenient style allowed women in the 20s to be able to do physical activities while still looking fashionable.

Left: Fashion Plates, 1926

Right: Greek Chiton – Source

South Asia

British India was arguably one of Britain’s most important colonies(20), so it made sense that Britain would take inspiration from Indian culture. Before we move on, let us take a look at Leyendecker’s painting again, this time keeping an eye out for Indian inspirations.

Top: Women’s head ornament from Uttar Pradesh, India, C.E 1800-50 – Source

Bottom: A close-up of a painting of a flapper by Frank Xavier Leyendecker, 1922 – Source

While the ornament on the left is not an earring, it bears a lot of resemblance to the earrings depicted in the painting.

Left: A common style of Indian head ornament – Image by Sumita Roy Dutta – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Right: A close-up of a painting of a flapper by Frank Xavier Leyendecker, 1922 – Source

The round gemstone design in the centre of the outfit resembles common Indian jewellery designs, mainly necklaces and headpieces

Left: By Mydust – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 – Source

Centre: Cora Laparcerie, 1921 – Source

Right: An illustration of a woman wearing a turban, 1924 – Source

The turbans on the middle and right are clearly quite influenced by the one on the left. Turbans were a common accessory in India, often associated with high class or even royalty(22). The ones decorated with stones were more popular in the Mughal Era, whose connections to the Middle East(23) must have appealed more to the idea of Orientalism and exoticism in the 20s.

Left: Fashion Plate, 1920 – Source

Right: Indian Kaftan – Source

Kaftan-style dresses were popular as well. Kaftans were extremely popular in Asia and parts of Africa throughout history. Aside from the Indian kaftan shown above, they were worn in the Middle East, Russia and the Ottoman empire(25). The light and breezy feel of kaftans appealed to women in the 20s who wished to let go of the restrictive nature of traditional European clothing.

East Asia

Europe had been interested in East Asia ever since the beginning of the ancient silk route. So, it made sense when 1920s fashion incorporated many elements of Eastern fashion.

Left: Fashion Plates, C.E 1923 – Source

Right: Jade Bangles for sale – Image by Salvador alc – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Plastic jewellery began to gain popularity in the 1920s as it became increasingly cheap after WW1. The public, unaware of the potential harmful effects of plastic on the environment, embraced it right away(8). In the post-war society, many people wanted to live a luxurious life but could not afford to do so, so plastic became a way to get the feel of luxury for cheap.

Left: A 1920s dress featuring chinese-inspired embellisments

Right: A Chinese woman wearing traditional clothes – Image by Eva Rinaldi from Sydney Australia – Chinese New Year, CC BY-SA 2.0

Red fabric with gold embellishments has always been a classic in Chinese culture. Red symbolizes happiness and fortune(24), two words also synonymous with 1920s society.

Left: A fashion plate, 1920 – Source

Right: Two girls wearing Hanfu – Image by Allervous – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

“Kimono-style” dresses were quite popular in the 1920s. Despite the name, they often took inspiration from other East Asian dresses as well, such as Hanfu. The flowy nature of these dresses appealed to customers of the time, and the silk offered the wearer a sense of luxury.

Conclusion

While all these different inspirations created a lively and exciting fashion scene, they often perpetuated stereotypes about these cultures. Other cultures were viewed as “savage” and “exotic”, leading Europeans to gain a sense of superiority. This does not mean that we should not take inspiration from other cultures; it simply means that we should try to get to know the culture first before playing by the stereotypes.

Bibliography

- Sweetman, John. The Oriental Obsession: Islamic Inspiration in British and American Art and Architecture 1500-1920. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002.

- Fiell, Charlotte. 1920s Fashion Sourcebook. Welbeck Publishing Group Ltd, 2021.

- Koda, Harold, and Andrew Bolton. “Paul Poiret (1879–1944).” Metmuseum.org. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/poir/hd_poir.htm.

- Fukai, Akiko, and Tamami Suoh. Essay. In Fashion: The Collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute: A History from the 18th to the 20th Century, 724. Koln: Taschen, 2002.

- Geczy, Adam. Fashion and Orientalism: Dress, Textiles and Culture from the 17th to the 21st Century. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2013.

- Davis, Mary E. Ballets Russes Style: Diaghilev’s Dancers and Paris Fashion. London: Reaktion, 2010.

- “Ballets Russes.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ballets-Russes-ballet-company.

- Gershon, Livia. “The Revolutionary Past of Plastics .” JSTOR DAILY, June 8, 2019. https://daily.jstor.org/the-revolutionary-past-of-plastics/.

- Satia, Priya. “British Orientalism.” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920 59, no. 1 (2016): 118-122. muse.jhu.edu/article/603466.

- Koda, Harold, and Richard Martin. “Orientalism: Visions of the East in Western Dress.” Metmuseum.org, October 2004. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/orie/hd_orie.htm.

- “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous in the Roaring Twenties Essay.” Bartleby. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.bartleby.com/essay/Lifestyles-of-the-Rich-and-Famous-in-FKCUD93CTJ.

- “America in the 1920s: Jazz Age & Roaring 20s (Article).” Khan Academy. Khan Academy. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/rise-to-world-power/1920s-america/a/jazz-and-the-lost-generation.

- Reddy, Karina. “1920-1929.” Fashion History Timeline, August 18, 2020. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1920-1929/.

- Dajani, Najat Z. J. Arabs in Hollywood: Orientalism in Film. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 2000. https://open.library.ubc.ca/media/stream/pdf/831/1.0099552/1

- “Movies, Radio, and Sports in the 1920s (Article).” Khan Academy. Khan Academy. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/rise-to-world-power/1920s-america/a/movies-cinema-sports-1920s.

- Thanhauser, Sofi. “A Brief History of Mass-Manufactured Clothing.” Literary Hub, January 27, 2022. https://lithub.com/a-brief-history-of-mass-manufactured-clothing/.

- Welters, Linda. Twentieth-Century American Fashion. Oxford: Berg, 2007.

- “Josephine Baker.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Josephine-Baker.

- “Entrance to King Tut’s Tomb Discovered.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, March 4, 2010. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/entrance-to-king-tuts-tomb-discovered.

- “Why Was India so Valuable to the British Empire?” BBC. BBC, November 9, 2012. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0167gq4#

- Bare, Eman. “Head Wraps Aren’t Just a NYFW Accessory.” Teen Vogue. Teen Vogue, September 15, 2017. https://www.teenvogue.com/gallery/head-wraps-nyfw-history-cultural-appropriation.

- Amin, Amit, and Naroop Jhooti. “From Mesopotamia to West London, a 4,000-Year History of the Turban.” CNN, February 15, 2019. https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.cnn.com/style/amp/turbans-tales-history/index.html.

- “Mughal Dynasty.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed December 7, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mughal-dynasty.

- Qiang, Huang. A Study on the Metaphor of “Red” in Chinese Culture, November 3, 2011, 99–101. https://www.aijcrnet.com/journals/Vol_1_No_3_November_2011/13.pdf.

- Hizkiyev, Ofir. “Kaftan.” Fashion History Timeline, March 19, 2022. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/kaftan/.

- “Ancient Greek Dress.” Metmuseum.org, October 2003. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grdr/hd_grdr.htm.

- Davis 2010, pp. 107.

- Davis 2010, pp. 110-111.

- Davis 2010, pp. 8.

- Davis 2010, pp. 93.

- Davis 2010, pp. 98.

- Fiell 2021, pp. 27.

- Davis 2010, pp. 100.

- Davis 2010, pp. 99.

- Gautier, Une Nuit de Cléopâtre, pp. 67-9.

cover image: A painting of a flapper by Frank Xavier Leyendecker, 1922