By Mahiba Arshia

Written: 18/03/2023

Updated last: 17/04/2023

Introduction

Among the various artists that shaped the 20th-century art world in America, Edward Hopper is one of the most renowned. Remarkable for his dreary landscapes, Hopper’s talent lies in his ability to create pieces which hold the power to invoke the sensation of empty loneliness. His work, albeit still and devoid of dramatic action, conveys an aura that only stillness can convey. The artist experiments with lighting, composition, and saturation in his landscapes to create diverse moods and tones.

Sources:

“From Williamsburg Bridge, 1928 – Edward Hopper.” Www.wikiart.org, WikiArt, 1 Jan. 1970, source . (left)

Seven A.M. 1948 by Edward Hopper, EdwardHopper.net, source. (right)

The piece ‘From Williamsburg Bridge’ (1928, oil on canvas) is an excellent example of Hopper’s talent in creating gloomy, almost unsettling atmospheres. ‘Seven A.M.’ (1948, oil on canvas) is another example where contrast is used to create a rather uncanny image. The early morning sun forms striking blue shadows on the bone-white storefront, which complements the greenery behind it. In contrast to the welcoming aura, the surroundings remain vacant and desolate; there are no people and the storefront itself has little merchandise (seemingly all random items) on display. The contrast here reflects and conjures an unsettling feeling throughout the painting.

These are only a few of the features that distinguish Hopper as one of the great American artists of the twentieth century. This article aims to detail further and explore Edward Hopper’s life, art, as well as how his style evolved into the classic that it is today.

Early life and Influences

Hopper was born on July 22, 1822, to a middle-class family in Nyack, New York City. Both his parents, Elizabeth Griffins Smith Hopper and Garret Henry Hopper were supportive of his artistic talents which themselves had bloomed brightly early on. His family gladly provided an environment for cultivating creative interests for both him and his sister with visits to theatres, museums and other cultural programs. Hopper was a calm and introverted young boy, spending the majority of his time with his books and art. Studying and sketching the construction of boats by the Hudson River became a hobby of the teenager, as indicated by the countless sketches and wooden models that commemorate his early youth. The importance Hopper gave to his art can be seen from his teenage years as he had started dating and signing his works by the age of ten.

Edward graduated high school in 1899 and continued his pursuit of art in his higher studies as well. Under the encouragement of his parents, the artist chose to seek a degree in commercial illustration rather than fine art at the New York School of Illustration in Manhattan(1899-1900). However, after merely a year there, he joined the New York School of Art (1900-1906) to chase after his love of painting. Here Edward Hopper received his primary influences from his teachers William Merrit Chase and Robert Henri. The impacts of impressions and Ashcan school in the creative’s work are rooted in his studies there. The idea of portraying urban landscapes through a more realistic lens rather than the glamorous romanticised cityscapes preferred at the time is a concept Henri encouraged greatly in his students. This resulted in Hopper’s common subject matter being urban commonplaces. However, unlike most artists in the Ashcan school whose paintings were more lively and full of movement(for example; most of George Bellow’s work), Hopper’s art embraces a sense of silent stillness. Moreover, the core of the ashcan concept is the rejection of the then-present American academic and aesthetic tradition which itself was seemingly a slave to European traditions. This rejection seeks to paint the “true” reality of America and express the unidealized everyday life of the people; to create an independent identity of America in art. This can be seen in Hoppers style, which at first glance has a very American feel to it. Impressionism too had a great impact on his early impressionable style. However, this impact only became even more significant to his art style throughout his travels in Europe.

Sources:

“The Cliff Dwellers, 1913 – George Bellows.” www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970. source. (top)

“The Barber Shop, 1931 – Edward Hopper.” www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970. source (bottom)

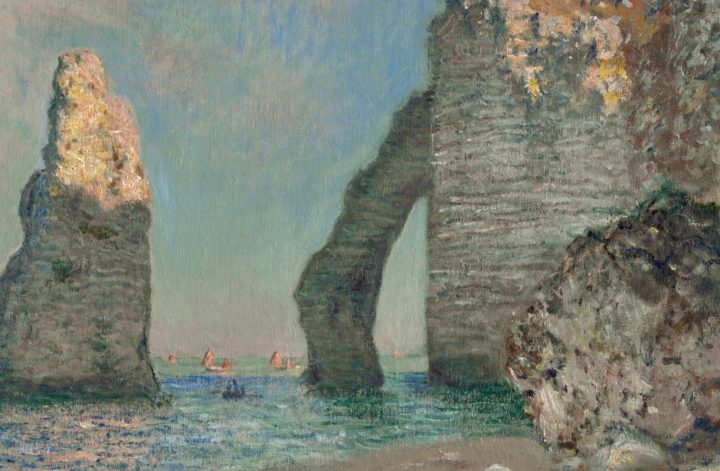

Edward completed his formal education in 1906. A year earlier he had taken up a part-time job illustrating while continuing to paint alongside. As traditional for art students at the time, he journeyed to Europe a total of three times from 1906-1910. Though he visited multiple countries, he stayed the most in Paris where the blooming styles of post-impressionism were further ingrained into his art. Several new styles such as Fauvism and Cubism rose to popularity during this time along with even Surrealism gaining steam among the artists of France. Nevertheless, his interest was piqued by none of the new trends that had arrived on the art scene but in the impressionist style of the 19th century. He was so enamoured by this style that later he admitted that, during his time in Paris, he had never heard of Picasso, one of the most significant artists of the modern art world.

His appreciation of artists like Edgar Degas, Edouard Manet, Paul Cezanne and even Van Gogh, and his reaction to the movement is directly reflected in his own work. A key practice that rose during the impressionism era was open-air painting or ‘En Plein Air’ and it is a practice Hopper became well acquainted with during his time in Paris. It is the process of painting landscapes outdoors and assists in paying attention to light and understanding the true colours of nature and atmosphere. The artist himself described this technique as a “from the fact” painting and used it in an attempt to collect details directly from the world around him.

Source: “The Exposition Universelle, 1867 – Edouard Manet.” www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1867 source

Source: “Gloucester Harbor, 1912 – Edward Hopper.” www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970. source

Throughout these excursions, Hopper sketched and painted outside, producing bright, roughly drawn cityscapes that assisted him in developing an understanding of how to frame the architectural environment around him. He admired the painters of this movement’s distinctive compositions of metropolitan settings and portrayals of contemporary urban life. Hopper admired Rembrandt’s Nightwatch on a visit to Amsterdam, calling it,

“ the most wonderful thing of his I have seen, its past belief in its reality – it almost amounts to deception.”

Source: “Le Pont Royal, 1909 – Edward Hopper.” www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970. source

The effect of his trips was displayed in his art which now made use of a lighter palette, and he started painting with delicate, rapid strokes. Though Hopper rarely painted with the pastels preferred by most impressionists the lessons about light, colour and compositing had an everlasting effect on his works. His excursions to Europe ended permanently in 1910, leaving him with one of the most significant changes in his style, which impacted the course of his profession for the rest of his life.

Early Career

[Sailing(1911)]

Source: “Sailing, 1911 – Edward Hopper.” www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970. source

Hopper’s career as a painter had a slow start. Fame did not fall easy on the young artist after his return to the States and remained that way for a decade. Upon his return, Hopper settled in New York City moving permanently to Washington Square North in 1913. The other notable event this year was the selling of his first painting. At the Armory show in NY, ‘Sailing’ (1911) was sold for $250. Unfortunately, despite the little recognition this show gained him, this was the last painting he sold for another decade.

Sources:

[Boy and Moon, 1906–1907]- Illustrationhistory.org. (n.d.). Boy and Moon.

Illustration History. Retrieved March 12, 2023, source (left)

[Evening Wind, 1921]- “Evening Wind.” Art Object Page. National Gallery of Art.

Accessed March 12, 2023. source (right)

[Au Louvre, la peinture, Mary Cassatt, 1876]

Source: wikicommons, here

During Edward’s strive for recognition, he found success in illustrations and etchings. Over a relatively brief amount of time, Hopper produced roughly 70 prints. His career as an etcher was fleeting, ending in 1923. He made two final drypoints in 1928 before abandoning printmaking to focus on painting. His etchings parallel similar themes of loneliness and melancholy which present themselves more clearly in his future more renowned pieces. This documents how his intention with art and what he wishes to convey has remained fairly the same throughout his career even through different mediums. His signature use of heavy lighting contrast is exemplified by the black and white of his etchings.

The clear inspiration for his pieces from this era came from Edgar Degas and Martin Lewis. ‘Evening Wind’ is a lovely reference to ‘Au Louvre, la peinture, Mary Cassatt’ by Degas noticeable by the similar execution of motifs of intimacy presented by the close spaces. The composition presents itself like the viewer is looking in into a very private moment of internal reflection and the sense of being lost in contemplation is another common trait. Similarly, Martin Lewis’s, who played a mentor figure for him, works share many distinguishing features with works of Hoppers such as ‘Night Shadows’ and ‘Night in the Park’.

[Martin Lewis, Relics (Speakeasy Corner),1928]

Source: “Martin Lewis, N.A. 1881-1962.” !-Martin Lewis. relics (speakeasy corner). etching.

Allinson Gallery, inc.–. Accessed March 12, 2023. source (left)

[Martin Lewis, The Great Shadow, 1925]“The Great Shadow.” Smithsonian American Art Museum. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Accessed March 18, 2023. source. Bequest of Frank McClure (right)

Lewis’s strong use of black vs white hard lighting adds to the composition and overall mood can be seen in Hopper’s art as well. Viewpoints are another similarity shared by the two artists share.

Despite his short run as a printmaker, this decade gifted the artist valuable skills which bloom brighter in his future works. Night Shadows (1921) with its birds-eye view, dramatic use of light and shadow, and an aura of mystery would inspire numerous film noir films of the 1940s. Over the years, Hopper garnered worldwide acclaim for his etchings, which he regarded as a crucial part of his artistic evolution. As he wrote,

“After I took up etching, my painting seemed to crystallize.”

[ Night Shadows,1921]

Hopper, Edward. “Night Shadows, 1921 – Edward Hopper.” www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970.source

In 1920, at the age of 37, Hopper’s painting career finally took a turn for the better. He showed sixteen of his original paintings at the recently founded Whitney Studio Club. Although none of the paintings here was sold, the exhibition gained him a fair amount of recognition. Although it was slow and quiet, Edward’s rise to popularity had started to begin.

Hopper makes his way to Gloucester, Massachusetts in 1923 where he is greeted by a familiar face. There he meets his former classmate, another fellow artist, Josephine (Jo) Verstille Nivision who was a public school teacher and respected painter.

[The Mansard Rood, 1923]

“The Mansard Roof.” Brooklyn Museum.

Accessed March 18, 2023. Museum Collection Fund

Upon her encouragement, Hopper picked up watercolour which ended up leading him to his next sale. Despite Massachusetts being renowned for being a place that fills artists’ minds with inspiration, the painter chose Victorian houses as his subject matter, instead of painting the Massachusetts surroundings. Further driven by Jo, he displayed six of his watercolour pieces in a show held at the Brooklyn Museum where he sold ‘The Mansard Roof’ (1923) for $100 to the museum itself. The sold painting itself was of a Victorian mansion on a bright sunny day with his signature hard lighting. “He captured the temperature of the air, a breath of wind, the rustling of dry grasses—an aura of timelessness very different from the psychic urgency so often found in his urban scenes,” said curator Mecklenburg. This particular style of the mansion was out of style and considered outdated at the time and Hopper’s choice of painting was due to that very notion. In a time of immense change and progress towards the future, depicting a mansion which would be considered a “vulgar style” then would be a symbol of the past; a reminder of the golden age of art and a rejection of modernism. This painting later became one of Hopper’s most well know watercolour pieces, a medium which he continued to paint even after his rise to fame.

Unstable Married Life; revealing a new leaf

Josephine Nivison Hopper, Self Portrait. Photo by Paul Mutino, courtesy of the Edward Hopper House Museum and Study Center, Nyack, New York.

In 1942, Hopper married Josephine. From then on, she became his primary model for female figures and his most enthusiastic supporter. Even when she was in her seventies, she was still his muse, though not often painted to an exact likeness as per his style. However, their marriage was not a happy or even successful one, despite staying together for the duration of their lives. Josephine herself was a young and ambitious artist but her marriage to Hopper was the decision that drowned her career. Hopper, no matter how great of an artist he was, was egotistical and envious of any recognition his wife received. He would actively go out of his way to never recommend her to any collector or museum, only introduce her as his wife. Besides Jo’s failing career, life at home was not easy for her either. Hopper was obsessive and abusive. He slapped her, “cuffed” her, scarred her, and bashed her head against a bookcase, according to Jo. He was scraped and “bit to the bone” by her. He would often insult and berate her over her art and rid her of her studio one year into the marriage. Their turbulent and often violent relationship discarded any energy and joy Jo had left to paint.

“Ed is the very centre of my universe…If I’m on the point of being very happy, he sees to it that I’m not. If I am happy ever and not too exhausted, I might want to paint….”

(Levin, p. 262)

The longer their relationship went on, the more miserable she became. Hopper detested her, to begin with, and soon into their marriage Jo too considered him an insufferable man who did not deserve to be called human. As her love of art died, she took up the role of Hopper’s secretary.

Josephine preserved meticulous records of Edward’s works, shows, and sales. She drafted his letters and proposed topics and headings. She gave him critical feedback, urged him to paint watercolours, and arranged props and poses for interior scenarios. Her role for him grew over time: she was now essentially his secretary, preparing every aspect of his displays, down to the lighting in the galleries. If his reputation was called into question, she became his supporter; most of all, she had the duty to cheer him up when he was exhausted, unhappy, and unable to work. At such moments, she would inspire him with her ideas, begin a painting, and paint until he felt inspired to pick up a brush and create himself.

Josephine had to live under Hopper’s shadow for the entirety of her uncelebrated and invisible career. Only after years with him did she realise that marrying Edward meant losing her identity as an artist.

After her death, she donated all of the remaining pieces done by both her and her husband to the Whitney Museum. Whitney kept all of Hopper’s works whereas disposed of those done by Jo. Some of her ideas and even pictures were credited to him wrongly.

Her life is an example of how hard it was for women to pursue a profession in the arts, more so if their partner was an artist as well.

“For the female of the species, it’s a fatal thing for an artist to marry, her consciousness is too much disturbed. She can no longer live sufficiently within herself to produce. But it’s hard to accept this.”

(Levin, p.246)

Two cannot be artists in one household; for the belief goes that rather than supporting each other they would compete and be envious of the other. Regardless of Jo’s sacrifices for her husband, she was the driving force for his most inventive and lucrative works. Without her, the greatest American realist would not be half as well known as he is today. To be unable to see her pictures today, which may have outperformed her husband’s in beauty, is a true tragedy for the world.

Josephine Nivison Hopper, Railroad Gates, Gloucester. Photo by Paul Mutino, courtesy of the Edward Hopper House Museum and Study Center, Nyack, New York. (left)

Josephine Nivison Hopper, Basket of Fruit. Photo by Paul Mutino, courtesy of the Edward Hopper House Museum and Study Center, Nyack, New York. (right)

The Decades of Stardom

In 1924, the Painter finally received enough acclaim to end his job as an illustrator. He had a solo exhibition of watercolours at the Frank KM Rhen Gallery in NY which ended up selling out entirely. His second exhibit received far more attention and an even larger crown as his name started gaining traction. The location of the exhibit helped its success as well. From here on Rhen Gallery continued to support and represent him for the rest of his life.

The following years came easier for the now fairly popular artist. As time went by, Hopper’s style grew and took the shape that is most recognisable by present-day viewers. Key motifs and themes which were expressed roughly in his earlier works, slowly but steadily, became portrayed more clearly. Elements ranging from lonesome characters in public or personal spaces to sun-soaked buildings, peaceful alleys, and seaside views with lighthouses were prominent concepts in his works, and these notions became linked with him in particular. Boxed perspectives, Strong and heaving lighting, simplified geometric lines and shapes — coupled with tense tones, and almost uncanny settings give the impression of surreality even though the physical features are anchored in reality, and people who are lost in their minds, at the centre of it all; these are all defining features of his art that blossomed during this period.

Sources:

“Night Windows, 1928 – Edward Hopper.”

www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970.

source. (top)

“Two on the Aisle, 1927 – Edward Hopper.”

www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970

source (bottom)

One of his best-recognised piece, ‘House by the Railroad’ (1925), was the first painting to be in possession of the recently established Museum of Modern Art in 1930. This painting was a high point in Hopper’s career due to its acquirement not only being an enormous milestone. The picture itself is a perfect encapsulation of Hopper’s style from the cinematic perspective, the slightly toned-down colours and even the harsh shadows. It is a representation of almost all elements of his style and his own personal artistic identity.

Source: “House by the Railroad, 1925 – Edward Hopper.”

www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970. source

source: “Cape Cod Afternoon, 1936 – Edward Hopper.” www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970.

source.

Hopper’s commercial success continued on through the 1930s with sales to major museums and even receiving a retrospective from the Museum of Modern Art in 1933. Praise was poured on the artist during this period of his as his art grew to be identifiable. The audience enjoyed the mature style of his pictures; a gateway to the past appreciation for realism when modern forms of art took over the industry. The stunning vistas he designed, the quiet dwellings and empty spaces he crafted, and the transitory effect that many of his works addressed gave a feeling of modern living and a new look that many in the art world appreciated, and many applauded him for this distinctive personality he had created in his artistic expression.

Source: “Nighthawks, 1942 – Edward Hopper.” www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970. source

The wartime and political disruption during the 40s did not hamper Hopper in his creative pursuits much. It was quite the opposite, as during this period it seemed he thrived, creating one of his most well-known paintings ever; ‘Nighthawks’ (1942).

In this picture, there are four customers and a server in a brightly illuminated diner at nightfall. The diner itself seems to be rather unpopular given only four people are present at this late hour and the street is entirely empty. The door to the restaurant cannot be seen by the viewer and the painting itself has the viewpoint of an outsider looking in; looking in and catching a moment where people are most vulnerable lost in thoughts. The people though how close they are, seem not to be conversing; they are sitting in silence. The sense of silence exudes through this painting as an uncomfortable feeling of dread hangs in the atmosphere. Despite being in a place thats meant to be livelily and surrounded by people, the figures can’t help but feel alone. The bright shine of the lamp in the diner is not enough to light the everlasting darkness outside. This painting was created at the height of the Second World War and in that context, it’s understandable why it became so popular. It held up a mirror to the anxiousness and fear present in the minds of the people. The feelings of alienation and vulnerability were something the people of the time were all too familiar with; so, it makes sense why they could resonate with this piece as well as many of his other works which often focused on those exact feelings.

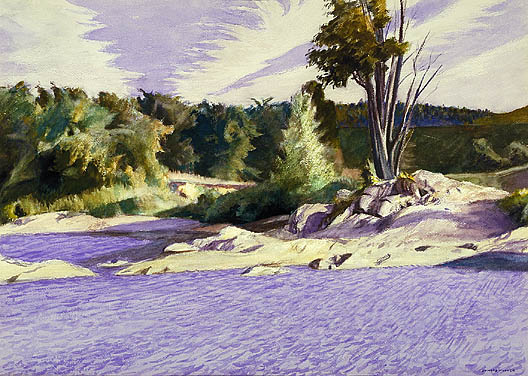

Between the 1930s and 1950s, Edward Hopper and his spouse spent a lot of time, especially during the summers at Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Many of the places that they visited were frequently visible in the art forms that Hopper made during this period. He subsequently began to travel further afield, visiting regions ranging from Vermont to Charleston, to add new points of interest to his collection and broaden the works and locations that he would incorporate in many of his artworks throughout his career.

Source: “White River at Sharon, 1937 – Edward Hopper.” www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970. source

Over the 1950s and 60s, Hopper fell out of favour. Although he always had an audience, even in this period, his prior exponential growth in popularity plateaued. With the arrival of new and exciting new schools like Abstract expressionism, pop and minimalism, his art no longer appealed to as many people as it once did. It would be a discredit to say he didn’t hold his own as he painted and displayed his work in exhibitions, though at a much slower rate, till he died. However, new kinds of art had taken over, and he, like many other painters before him, had gone out of fashion with critics.

Edward Hopper died on May 15, 1967, only ten months prior to the death of his wife. Both he and Jo are buried in Nyack’s Oak Hill Cemetery, among his sister and parents.

Style

An American Realist

Almost all of Hopper’s works fall under the category of realism. His identity as an American realist painter is what he gained recognition for. Although, as a former student of Robert Henri, this comes as little surprise given that Ashcan School is widely considered an ancestor of the realist style. However, there are certainly some key differences between his and his formal mentor’s works as well as ideals.

American nationalism, to some degree, is fundamental to American realism. The belief was that American art should deal with the realities of America and the lifestyle present there. America must be integral to and the centre of American realist art. Yet many of the early realist painters, including Robert Henri, were against this notion, believing instead that

“American art could only arise through the free expression of the individual spirit.”

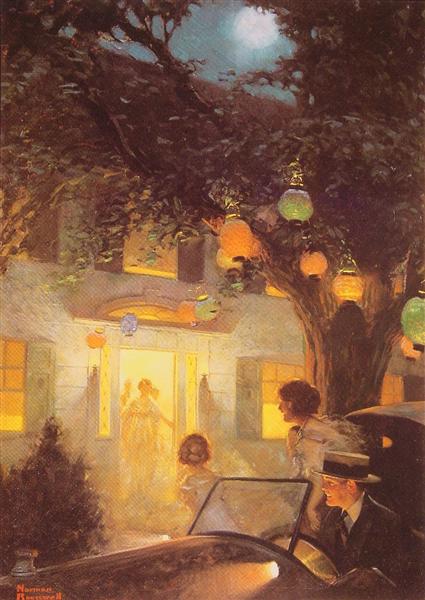

Source: “And the Symbol of Welcome Is Light, 1920 – Norman Rockwell.” www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970. source.

Edward Hopper, although inheriting some of this theoretical idealism, viewed the world a bit differently. Gaining popularity during the years of growing nationalism, he was far keener on Americanism. While the early realists battled for American painting as a whole, later painters fought to turn the subject into America itself. This explains the immediate feel Hopper’s paintings possess. Even a stranger to any knowledge of the man and his work can detect something incredibly “American” about them.

It’s similar to how the works of Norman Rockwell have essentially, an American sensation to them, although done very differently. Whereas Rockwell captured and told the story of idealistic, quaint, or sentimental portrayals of American life, the America in Hopper’s work is quieter, more lonesome, and portrays the stillness and inherent sombre present in daily American lives. Hopper paints the most ugliest and depressing pieces of provincial aspects of American life, and even so, his art depicts Americanism just as much as Rockwell’s more optimistic and joyful pictures do.

source: “Eleven A.M., 1926 – Edward Hopper.” www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970. source

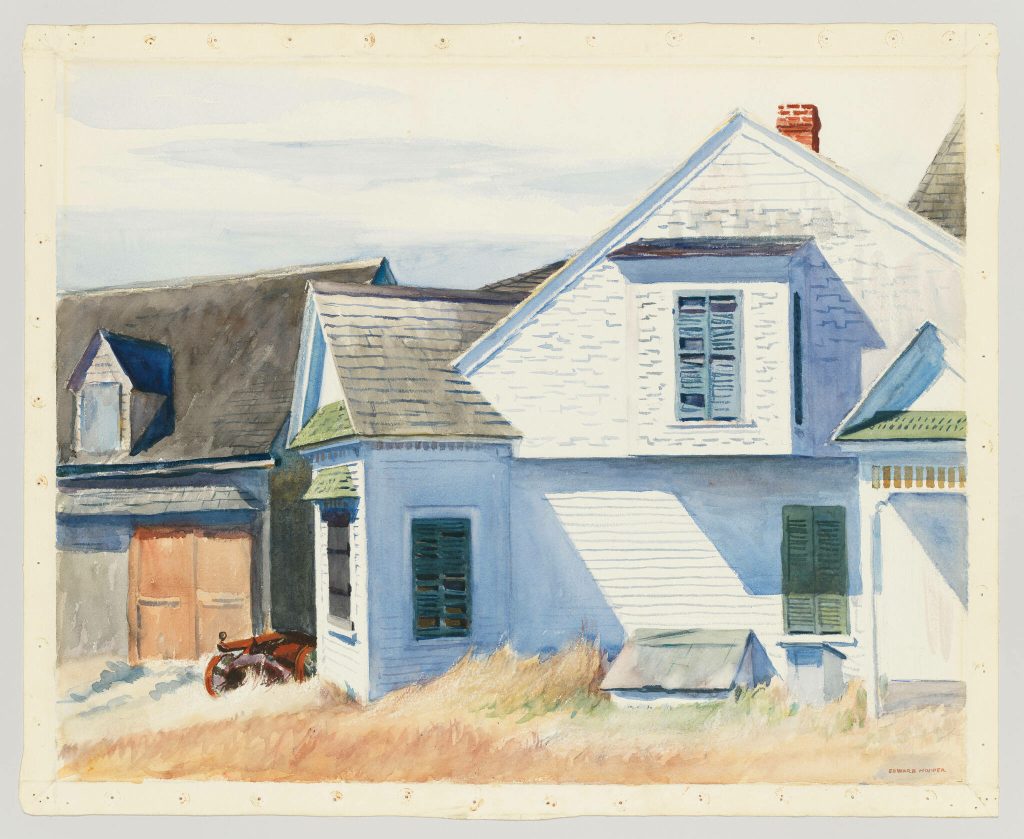

Watercolours and Workflow

Source: Edward Hopper (1882–1967), House on Pamet River, 1934, Watercolor and graphite pencil on paper, Sheet (Irregular): 21 13/16 × 26 13/16in. (55.4 × 68.1 cm),Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Despite being known for his oils, Hopper’s career first started off through his watercolour. There’s a very clear distinction between his famous oil pieces and watercolours. The man found freedom away from the big city, sitting down to paint the natural world around him with quick strokes as the medium requires. He painted from life and the complex world around him which stood in contrast to previous etchings and paintings, which were mostly imagined by himself rather than a replica of what existed. It is in this era that he found Victorian houses and lighthouses as symbols of the past.

By juxtaposing these portraits with power lines, train tracks, or other markers of development, he generated a connection between the past and the present and alluded to change as a basic feature of American life. As the years went on and his experience grew, a visible change occurred in his works. The thirties witnessed watercolours which were more precise than spontaneous. His later works came to feature more texture than their predecessors through the means of dry brushing.

Hopper’s painting process is another thing to note, considered particularly unique in its precision. Thus came the habit of rigorous sketching, studies and observation of the subject in its environment. To best illustrate this, stands ‘Hopper Drawing’ at The Whitney Museum (or more so the immensely detailed documentation of it online) shows the artist’s steps in preparing for his paintings.

Source: Edward Hopper (1882–1967), Couple Drinking, 1906–07. Transparent and opaque watercolour, graphite pencil, and fabricated chalk on paper, 13 1/2 × 19 7/8 in. (34.3 × 50.5 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.1340.

In an interview with John Morse in 1959, Hopper expresses his desire to accurately recreate his personal impression of the world. In a statement by him written in 1933, called “Notes on Painting”, he explains (in the interview) that throughout his career that has been his central goal. He states:

“ My aim in painting has always been the most exact transcription possible of my most intimate impressions of nature.”

The painter’s wish for exactness is fulfilled through his use of numerous sketches and noting details which, although wouldn’t make the piece less impressive, certainly adds life to it. His love and dedication to his craft are visible in his work process. According to Carter E. Foster, the show’s curator, Hopper would frequently make multiple excursions to the locations of his works, collecting details that would serve as essential references when painting in his studio. For his “ Room for Tourists,” he made two sketches, one during the daytime and the other at night. This exercise expresses hoppers experimentation with his key element, lighting. The mood shifts between the two pieces with the latter expressing the hopper’s go-to motif. Foster’s observation emphasises a feature of the broader painting process: decision-making. By drawing sketches, Hopper was able to experiment with various renderings, all of which supplied information that contributed to the final decision-making process.

Sources: Edward Hopper, Study for Rooms for Tourists, 1945. Fabricated chalk and charcoal on paper, 10 3/8 × 16 in. (26.4 × 40.6 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.438.(left)

Edward Hopper, Study for Rooms for Tourists, 1945. Fabricated chalk and charcoal on paper, 15 × 22 1/8 in. (38.1 × 56.2 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.848 (right)

Source: “Rooms for Tourists, 1945 by Edward Hopper.” Rooms for Tourists, 1945 by Edward Hopper. Accessed April 2, 2023. source.

Due to his inability to paint on-site, Numerous of his sketchings also includes annotations and notes on shadows and colours, like “greenish” and “ruddy light” written next to scenes. These reminders allow the artist to remember and learn not only the details of the location but also better understand the mood it creates, altering it to how he wants to shape it. At the same time, some of his sketches are reminiscent of architectural drafts, most likely a skill he acquired during his youth when he would spend his time drawing boats and such. Notes on the state of lighting and how it falls on the building portray the critical observations made by the master. Despite his painting’s immense detail, it’s the open-ended curiosity they produce that makes them enticing. Even in the stillness a sensation of suspense, a moment to hold one’s breath and it is that moment that captures the audience to keep their gaze.

Hopper’s touch

Sources:“Hotel Lobby, 1943 – Edward Hopper.” www.wikiart.org. WikiArt, January 1, 1970. source

“Alienation”, “silent” and “timeless” are the terms used in almost every critique and article regarding Edward Hopper’s works. These are words most viewers would agree with to describe the picture; the silent dense sombre air of “Nighthawks”, and the visible alienation felt not only by the characters but also (to some extent) by the viewers who seem to be merely looking into a scene they have no part in, in “Hotel Lobby” and the uncanny timelessness that the “house by the Railroad” presents. These words express the emotional and psychological response to his work and more so how universal these three emotions implied, are.

Throughout his works, Hopper has shown consistency in his values and their relation to the composition and its design. He uses light tones in the front and deeper tones in the mid and background without much variation. Thus background objects don’t necessarily “fade” into the background but rather layer like sets on a stage. At times, some objects contrast their layers in order to stand out and “break” the horizontality. The use of brilliant contrasts in order to set the mood and design stands to be one of Hopper’s most defining traits. The apparent illusion of three-dimensional depth is achieved through forms in relation to each other.

The creative’s colour palette is another consistency in his work. Lighter warmer colours are present in the foreground and darker cooler in the back. However, the saturation of the pieces is dependent on the local colours of the object as light falls on it. The sharp lighting and the contrast it creates can oftentimes leave the viewer in a moment of awe, enough to parallel the poignance of movement. The stillness of the subjects can be contrasted with the footprints left by the brush. The almost “patchy” paintwork suggests movement in places and thus creates an uncanny antithesis to further suit the mood of the work. Conversely, it also adds to the silent stillness of the scene as the flow developed by the brushwork, much like a foil character, emphasises the lack of it.

Another interesting aspect is the sense of alienation. He achieves this in a multitude of ways the most obvious of such being isolation. “automat”, “Hotel room”, and “Sunday (1926)” along with many others feature simply a character entirely alone with hazy eyes lost in either action or thoughts. In these paintings, the perspective is always of an outsider looking in, a witness to the sombre beings. There are cases where the figures are not alone yet it doesn’t make a difference.

Source: Edward Hopper, Soir Bleu, 1914, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

“Soir Bleu”, “Room in new york” and “Nighthawks” are prime examples of this case. In each of these, there is no human connection between the characters, all of whom are stumbling in deep thought. They are essentially disconnected from theur surroundings, a sight that the viewer carries over from the painting. It matters not how beautiful the scene is if the vocal character cannot bring themselves to care about it. The apathy regarding the world around them essentially, and even subconsciously, plants the idea that it is not worth caring about. There lie Hopper’s ideas of contrast; the viewer can care but the character cannot, enabling the visible isolation and disconnect. It shows the fragments of an experience. There is also detachment from time itself. At times the characters can feel stuck in a time, preoccupied in their mind, while the world moves on; further pushing that feeling of alienation.

Lastly, a method to elicit such reactions that have been applied here is the stubborn yet effective wish to not romanticize the mundane but to present it as it is and as the artist interprets it. In scenes where there should be joy like a diner or on the face of a clown, theres tragic yet real melancholy. This is the very essence of realism. Edward Hopper’s identity as a realist painter thrived determinedly in a time of abstract and modern change, and his ideals were made through till the end.

Bibliography

- “Edward Hopper.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., March 7, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edward-Hopper.

- “Edward Hopper and His Paintings.” Edward Hopper: 100 Famous Paintings, Biography, and Quotes. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.edwardhopper.net/.

- Murphy, Jessica. “Edward Hopper (1882–1967): Essay: The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.” HEILBRUNN TIMELINE OF ART HISTORY. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, June 1, 2007. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hopp/hd_hopp.htm.

- “Edward Hopper.” Edward Hopper | Whitney Museum of American Art. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://whitney.org/artists/621.

- Edward Hopper. National Gallery of Art. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.nga.gov/features/slideshows/edward-hopper.html.

- “Edward Hopper Paintings, Bio, Ideas.” The Art Story. The Art Story. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.theartstory.org/artist/hopper-edward/.

- V, Ruthie. “Hopper’s Influences in Painting.” Seattle Artist League. Seattle Artist League, November 15, 2018. https://www.seattleartistleague.com/2018/11/15/hoppers-influences-in-painting.

- Vance, Heidi. “Edward Hopper: Get to Know the King of American Realism in 15 Facts.” TheCollector. The Collector, September 13, 2020. https://www.thecollector.com/edward-hopper-artist-painter/.

- Gutierrez, Iliana. “Edward Hopper: Precision through Process.” NOBLE OCEANS. NOBLE OCEANS, April 5, 2017. http://www.nobleoceans.com/artists/2017/4/2/edward-hopper-precision-through-process.

- Khalid, Farisa. “The Ashcan School, an Introduction (Article).” Khan Academy. Khan Academy, 2014. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/american-art-to-wwii/ashcan/a/the-ashcan-school-an-introduction.

- “ The Ashcan School and The Eight.” Robert Henri Museum. Robert Henri Museum and Art Gallery. Accessed April 6, 2023. https://www.roberthenrimuseum.org/ashcan-school.

- Kantrowitz, Jonathan. “Edward Hopper: The Watercolors.” Art History News, June 6, 2012. http://arthistorynewsreport.blogspot.com/2012/06/edward-hopper-watercolors.html.

- Plötz, Senta Trömel. “Josephine Nivison-Hopper.” FemBio . Accessed April 6, 2023. https://www.fembio.org/english/biography.php/woman/biography/josephine-nivison-hopper/.

- WILLIAMS, ADELIA V. “‘Poésie Critique’ as ‘Poetics of Space’: Edward Hopper and Claude Esteban.” Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal 31, no. 4 (1998): 123–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44029738.

- Nochlin, Linda. “Edward Hopper and the Imagery of Alienation.” Art Journal 41, no. 2 (1981): 136–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/776462.

- Hanson, Anne Coffin. “Edward Hopper, American Meaning and French Craft.” Art Journal 41, no. 2 (1981): 142–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/77646

- Stanton, Joseph. “ON EDGE: Edward Hopper’s Narrative Stillness.” Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal 77, no. 1/2 (1994): 21–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41178875.

- Brown, Milton W. “The Early Realism of Hopper and Burchfield.” College Art Journal 7, no. 1 (1947): 3–11. https://doi.org/10.2307/773539.

Cover image: Edward Hopper, Soir Bleu, 1914, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York