By Nayara Shah

Written on 30/12/2022

Last updated: 27/01/2023

At the beginning of the 17th century; the flourishing of the most well-known period of art, the Renaissance, was coming to an end. Though its classical style was popular all throughout Rome, the need for unnatural, stylised and ambiguous forms of art sparked the beginning of what we call ‘Mannerism’.[4]

Originating in the late 16th century, the word “Mannerism” is derived from the Italian word ‘maniera’, which simply translates to “stylish style”. Common characteristics that can be seen in style are elongated features, contrived poses, nude figures and unnatural colour palettes.[1] Features like this can be seen in arguably the most popular Mannerism painting, “Madonna with the Long Neck” by Parmigianino.

Madonna with the Long Neck by Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazola or Parmigianino, 1534-1540 C.E,Image via Wikimedia Commons

In this painting, Madonna, which refers to the representation of the Virgin Mary,[6] appears holding a nude, infant Christ on her lap.[5] As suggested by the title of the painting, she is seen to have an elongated neck, as well as fingers and shoulders. The distorted body parts are not the only features of Mannerism which Parmigianino highlighted in this painting; he paid attention to his own contemporary ideas of feminine beauty, which is incorporated into the depictions of Madonna as well as the other women present in the painting.[4] Additionally, the painter incorporated a sense of eroticism, which is shown by the fabric draped around Madonna, highlighting her curves, her hand lifted to her chest, and the bare leg of the angel on her side.[5]

In 16th Century Rome, High Renaissance artists like the famous Leonardo Da Vinci, Raphael, Michelangelo, etc. set the standard for classicism and idealised beauty. It was the norm to depict a formal sense of complexity in nude figures, which was specifically set by Michelangelo. However, when Mannerists began to succeed these artists, they put more importance into the figural composition along with their style and technique than the actual meaning, symbols or importance behind the subject matter of their paintings. Breaking away from the boundaries set by Renaissance painters, Mannerists thrived in depicting physical distortions, artificial poses and a bizarre yet elegant compositions.[1]

Mannerism was essentially born as a rejection of harmony, therefore Mannerist artworks depict what seems like a different reality from our own, beyond the confines of literal correctness. They achieve this by developing radical asymmetry, artifice and a bizarre colour palette in their works. Their goal to stray from the classical influences of the Renaissance resulted in the expressive, dramatic and anti-traditional style, which was later divided by some scholars into two; Early Mannerism and High Mannerism.[3]

Early Mannerism is referred to as the style used in paintings created right after the reactionary birth of Mannerism, while High Mannerism describes the style after it was refined to appeal to the more sophisticated of patrons. While the anti-tradition of Early Mannerism lasted till around 1535 CE, High Mannerism went on to be used as a type of court style.[3]

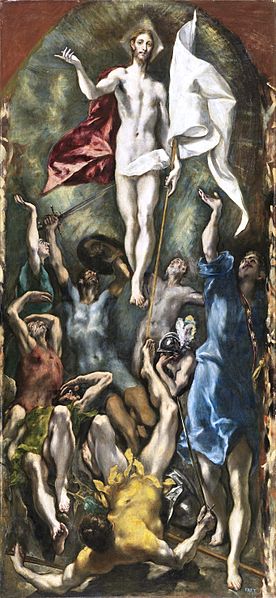

Resurrection by El Greco, 1597-1600 C.E,Image via Wikimedia Commons

Amidst the rise of Mannerism’s successor, the Baroque art style, one of the greatest Mannerists, El Greco, created what he called, “Resurrection”. Due to his Cretan heritage, El Greco’s works are considered by some to be a form of Byzantine art as well.[7] However, as Jesus Christ is seen whisking the figures at the bottom of the painting up towards the heavens, his High Mannerist inspirations are the most striking in his work. The bold colours, intense drama and physical distortions are what solidify El Greco as a Mannerist. The intricacy of light and shadow, along with the extreme proportions and acidic colour palette, are what laid the grounds for modern artworks, for centuries to come.[4]

What appears to experts in the 21st century as one of many historical art styles waiting to be studied, was once the catalyst for greater freedom in art and a powerful extension of the Renaissance,[2] forged with creativity, rebellion, and most importantly; human expression.

Bibliography

- “Mannerism.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed December 29, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/art/Mannerism.

- Mannerism. Accessed December 29, 2022. https://www.nga.gov/features/slideshows/mannerism.html#slide_1.

- “Mannerism Movement Overview.” The Art Story. Accessed December 29, 2022. https://www.theartstory.org/movement/mannerism/.

- Hodge, A. N. “The Baroque Era.” Essay. In The History of Art: Painting from Giotto to the Present Day, 50–51. London: Arcturus, 2009.

- “The ‘Madonna with the Long Neck’ by Parmigianino: Artworks: Uffizi Galleries.” The ‘Madonna with the long neck’ by Parmigianino | Artworks | Uffizi Galleries. Accessed December 29, 2022. https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/parmigianino-madonna-long-neck.

- Doniger, Wendy. Essay. In Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia of World Religions; Wendy Doniger, Consulting Editor, 696–96. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, 1999.

- “Resurrection.” Resurrection by El Greco. Accessed December 29, 2022. https://www.thehistoryofart.org/el-greco/resurrection/.

Cover image: The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, Painting by El Greco